A Field guide to EXIT ZERO:

Urban Landscape ESSAY FILM, 1921 till Now

dissertation PROSPECTUS

Still from Organism, dir. Hilary Harris, 1975, 19m.

LANDSCAPE

The word landscape comes to English from the Dutch, “landscap” meaning to shape the land. This meaning evolved into a picture or a view of the land, or as geographer and Landscape Magazine editor J.B. Jackson explains “a landscape is a portion of land which the eye can comprehend at a glance." Jackson explains that in America, we tend to think of landscape as referring to only natural scenery, whereas in England, a landscape almost always contains a human element.

In this dissertation, I use the term landscape in an expansive way. Landscape is both a view and a picture but for my purposes, I also regard landscape as an orientation toward the act of representation.

Practically everyday we are confronted with the idea of landscape as an orientation, one of the two choices of an inescapable binary — the landscape vs. portrait — a binary embedded in our everyday interactions with our technological handmaidens — the cellphone, the tablet, the computer printout. The omnipresent rectangle of the visual frame is so naturalized into the experience of our screens, it seems almost silly to call attention to it. But, what I want to suggest, is that the difference between the portrait and the landscape, is not simply a difference in screen orientation, but can also be thought of as a difference in orientation toward the concept of subjectivity itself.

For many years longer than the cell phone has been around, the wideness of one’s screen has been assumed, at least in the commercial film context, to determine a media’s value, defined as the potential for maximum immersion. Another way to think about immersion is a film’s ability to make viewers forget themselves, forget their own subjectivity and enter into the film’s perspective or the film’s diegesis.

“Landscape is looking at a view, which makes you see yourself seeing.”

WJT Mitchell writes that “landscape is looking at a view which makes you see yourself seeing.” In other words, landscape is a form which brings awareness of one’s own subjectivity into consciousness. It implicitly raises the questions: who’s view is this and why am I looking? In his survey of experimental landscape films, Scott MacDonald suggests that experimental landscape films made in the 1970s, devoid of human activity and narrative, and focused exclusively on landscape for extended durations, could be viewed as a form of critique of commercialism— both a critique of Hollywood and of the increasing materialism of 20th century capitalist culture.

Still from Fog Line (1970), directed by Larry Gottheim.

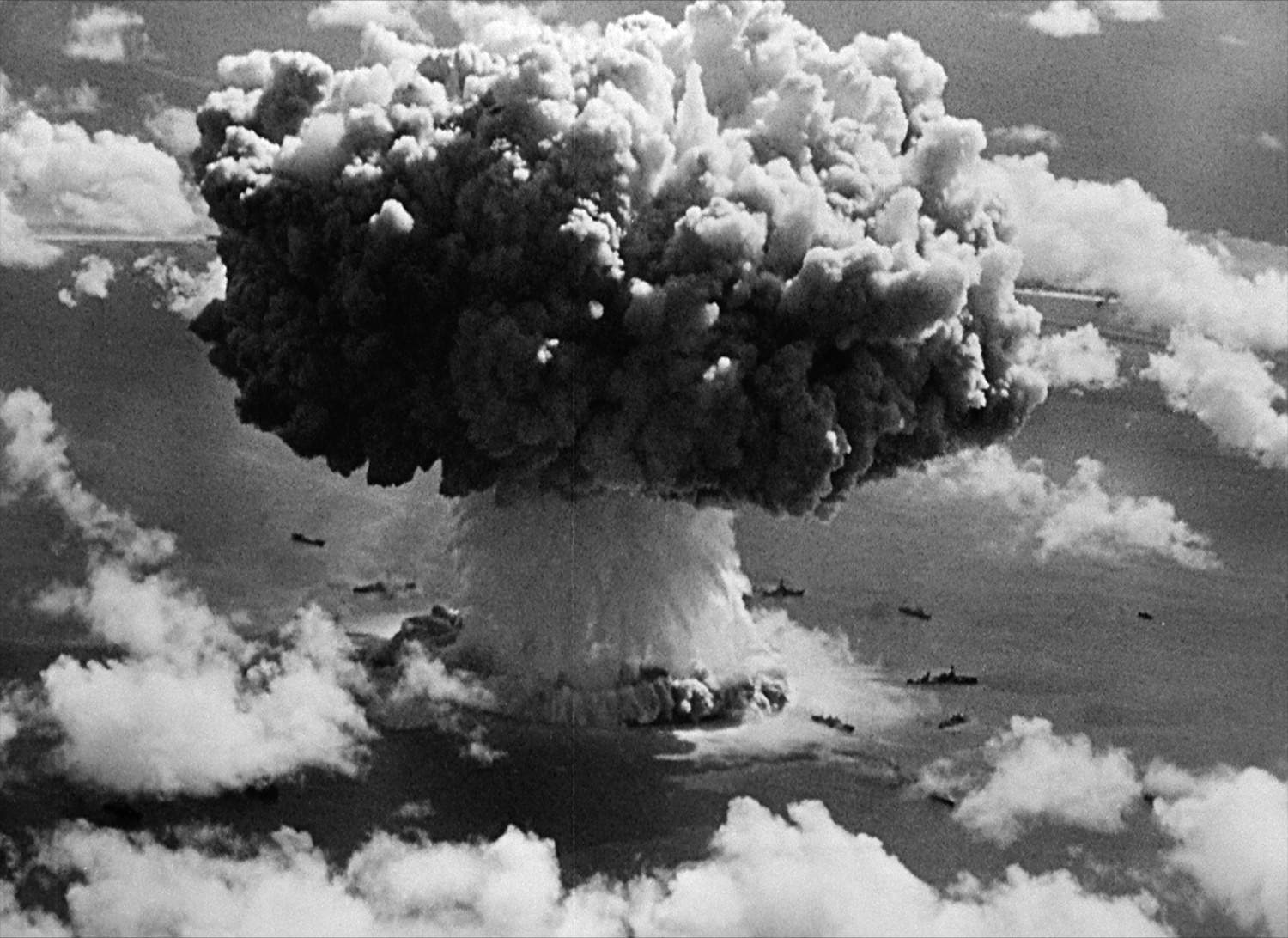

Still from Crossroads, directed by Bruce Connor, 1976.

Analyzing nonfiction filmmaking practices in which place is the subject of a film, and not simply it’s setting, I explore the kinds of political and cultural work that landscape documentary filmmaking offers. Working with the conception of landscape as a wide view, impersonal and “objective,” this dissertation engages with a fundamental representational problem that landscape media presents: how does an audience relate to a moving image experience without a singular protagonist to identify with? In this way, my work challenges the notion that moving image subjectivity is fundamentally the viewpoint of an individual; arguing for a radical and politically engaged understanding of landscape documentary practices which offer alternatives to the kind of subjectivity that we are trained to expect and predisposed to want in our capitalist society.

Landscape films, like the surprisingly commercially successful Koyaanisqatsi from 1982, provide us with a kind of subjectivity of place, offering experiences of the ways that place can reveal structures and patterns of collective activities, both human and nonhuman. The landscape orientation insists on a kind of horizontality of attention and subject, challenging and breaking down the hierarchies of attention — maybe even undermining the way we are generally taught to think about the meaning of “subjectivity” itself. Jonathan Kahana, has written that the original city symphony films, such as Man with a Movie Camera and Berlin Symphony of a Great City provided a modernist form of public subjectivity. Koyaanisqatsi expands the day in the life structure of the city symphony form to portray, with the help of tour-de-force time-lapsed cinematography, a kind of machine-enabled public, national subjectivity of life out of balance.

“Big Blue Marble,” 1972, photograph from Apollo 17 moon mission

A number of historians of the environmental movement have credited the image of the Whole Earth, with changing environmental consciousness and providing us with an image of ourselves as a global entity, precariously alone in space, on one shared planet. I would argue that this whole earth image, can be understood as a landscape, a view comprehended at a glance, which has functioned culturally as a critique of both capitalism and individualism. And, just as technological development and scientific innovation is responsible for enabling and disseminating this globalized viewpoint, new technological developments in communications media are also allowing us to represent and share a multiplicity of viewpoints and collective perspectives in new ways, facilitating new forms of crowd subjectivities.

For example, we can think of the use of hashtags in platforms such as Twitter and Instagram as functioning like a new kind of montage machine. Retooling Alex Juhazs’s proposition that Facebook could be thought of as a new kind of documentary, hashtags such as #NoDAPL on Twitter provide a constantly changing documentary of the demonstrations against the Dakota Access Pipeline in Standing Rock, North Dakota. This kind of aggregation of a large range of perspectives expresses a new kind of horizontality in both subject formation and form, or what I think of as a kind of 21st century landscape orientation to subject. To build upon Jaimie Baron’s theory of the archive effect, I think of this horizontality as comprising both temporal horizontality, meaning a horizontality of time and sequence as well as an intentional horizontality or, in other words, the appropriation of many different viewpoints or perspectives —suggesting a social or cultural horizontality in terms of shared authorship and collective forms of authority.

These sorts of contemporary expressions of landscape orientations and landscape aesthetics are breaking out against an otherwise still dominant portrait mode in mainstream and commercial documentary practices. The primacy of individuality which has so dominated our previous cultural era still holds a strong grip over media-making, holding on, as it were, to their last gasps of relevancy— yet, I would argue, still exerting a huge pressure on commercial documentary filmmaking. This is particularly true for environmental films - here both of these recent films, have been marketed as the next An Inconvenient Truth. Both are attempting to sound the alarm and reach mainstream audiences with their environmentalist messages, and both are mired in these structures of the single, celebrity protagonist as film tour guide and central consciousness, as was the Al Gore film which came before it…. These films, which lean on a celebrity central consciousness, misdirect our attention onto the trajectory of the individual as change maker, and miss opportunities to embed a shifting of consciousness of collectivity and the power of collective action into the very aesthetic fabric of the film.

Another example, of the struggle between the landscape orientation and the portrait in documentary is the recent “award winning” film The Overnighters, which received an Oscar nomination for best documentary last year. It’s a film which starts out taking a cross-sectional landscape approach to representing the economic and social transformations brought about by the oil boom in one town in North Dakota.

Yet, mid-way through, it suddenly takes an unexpected, right-turn and becomes fixated on the character of the local pastor, who, it is dramatically revealed, is a closeted gay man, grappling with his own terrible secret. As the film questions this character’s personal motivations for his actions, any ability to explore and critique the structural issues around the oil boom and the social, economic and environmental issues caused by the oil industry are hijacked. Even the call at the end of the trailer to give money to a non-profit organization to fight homelessness is a kind of neoliberal assertion that charity should bare the burden for dealing with the crisis of homeless, rather than any attempt at holding the real responsible party, the oil industry, to task for the social, environmental and economic problems the film could have focused on.

In her book, Crowds and Party, Jodi Dean describes the essential paradox of the ways in which “capitalist processes simultaneously promote the individual as the primary unit of capitalism and at the same time “unravel the institutions of solidaristic support on which this unit depends.” She argues that it is the individual form itself which impedes collective political subjectivity and she ties the disenfranchisement of progressive and left wing politics, in the US and beyond, to the ways that our concept of subjectivity has been captured and enclosed by the ideology of individuality.

In counter-logic to how individuality and radical politics has often been understood, with individuality being synonymous with personal freedom — Dean suggests that the individual is a form of capitalist capture which “reduces agency to individual capacity, freedom to an individual condition and property to individual possession.”

Writing about postmodern documentary in the ‘90s, documentary scholars such as Bill Nichols and Michael Renov, pointed to a shift in documentary which begins in the late 1960s, away from the representation of social movements and towards a personal is political ethos in which “truth” was framed as personal, contingent and subjective.

Even horizontal, cross-sectional films like Word Is Out, from 1977, where the film is constructed entirely from interviews of many different people — represent an ideology of individual portraiture in which everyone is different, even if they are all gay…. and argues that there is no one or even no collective truth — but rather a collection of individual truths and a diversity of individuality, asserting that there is no one truth for what it means to be gay.

A Materialist Critique

for the Critique of Realism

Fast forward to the first decade of the 21st century. In writing about An Inconvenient Truth, Charlie Musser notices a shift in the politics of the term “truth,” suggesting that Al Gore re-inscribes the relevancy of scientific data and methodologies, as well as an agreed upon notion of truth itself. Musser writes that the Bush administration’s denial of climate science places Gore in the position of rhetorically asserting truth and reality over the state fictions of the Bush Administration. Here, the suggestion is that the post-modernist, contingency of truth is shifting in the face of overwhelming environmental issues.

So, thinking about this shifting relationship to subjectivity and “truth” is one of the theoretical jumping off points I will take in my research. Specifically, how do we reconcile the materialist, realist needs we have for documentary to represent collective social and environmental problems with our poststructuralist training which teaches us to critique the assumptions and aesthetics of objectivity, technology and science?

Still from “Berlin: Symphony of a Great City,” directed by Walter Ruttman (Germany, 1927)

Joshua Malitsky suggests that what we have come to regard as the “suspect political, ethical, and epistemological claims associated with pure objectivity” might better be understood as representation which coincide with forms of public knowledge. In this configuration, scientific truth is not some objective absolute, but rather a truth which can be derived through community consensus, whether scientific or other, which places the emphasis for meaning beyond individual verifiability.

As the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus once said, you can never step into the same river twice. And, I would suggest that rather than thinking about documentary as returning to some older reliance on objective forms of representation, we might instead view landscape documentary as providing “materialist” approaches to evidence and indexicality which assert, not so much a faith in objectivity and Science with a capital S, but rather provide various kinds of collective subjectivities.